The One In Which Oscar Isaac Is God - Ex Machina (2014)

Yeah, sure, I write things from a queer perspective far more often than I intend to. But I can write about other things…right?

You’ll…still read my stuff when I write about other things, right?

Now, that said, while I’m writing this, I’ll throw in a quick mention of Oscar Isaac being hot-as-fuck (albeit in a weirdly, changing way,. Regardless of what role he’s playing) and after that, I can move on to that being the only gay thing I can and will say about Ex Machina. (Oh, maybe add in “that’s not even the bearded Gleeson brother that I’m attracted to.” )

But yeah, that’s me, I’m done with the juicy bits of the content and I guess you can close the page now?

Or maybe you’ll keep reading…

Ex Machina from writer-director Alex Garland, was one of those films that I’ve wanted to watch for a while, but I saw as some thoughtful slow-burning study into the human condition, a film that could go a bit boring and meaningless. I’m not entirely sure why I’d think that; the guy has also given me Dredd (what a fucking brilliant movie) and worked on two of my favourite video games ever ( dmc: Devil May Cry and Enslaved: Odyssey To The West); for some reason, I keep forgetting these things, and then I act all surprised and shocked when I read or see them as if I’ve never read or seen them before.

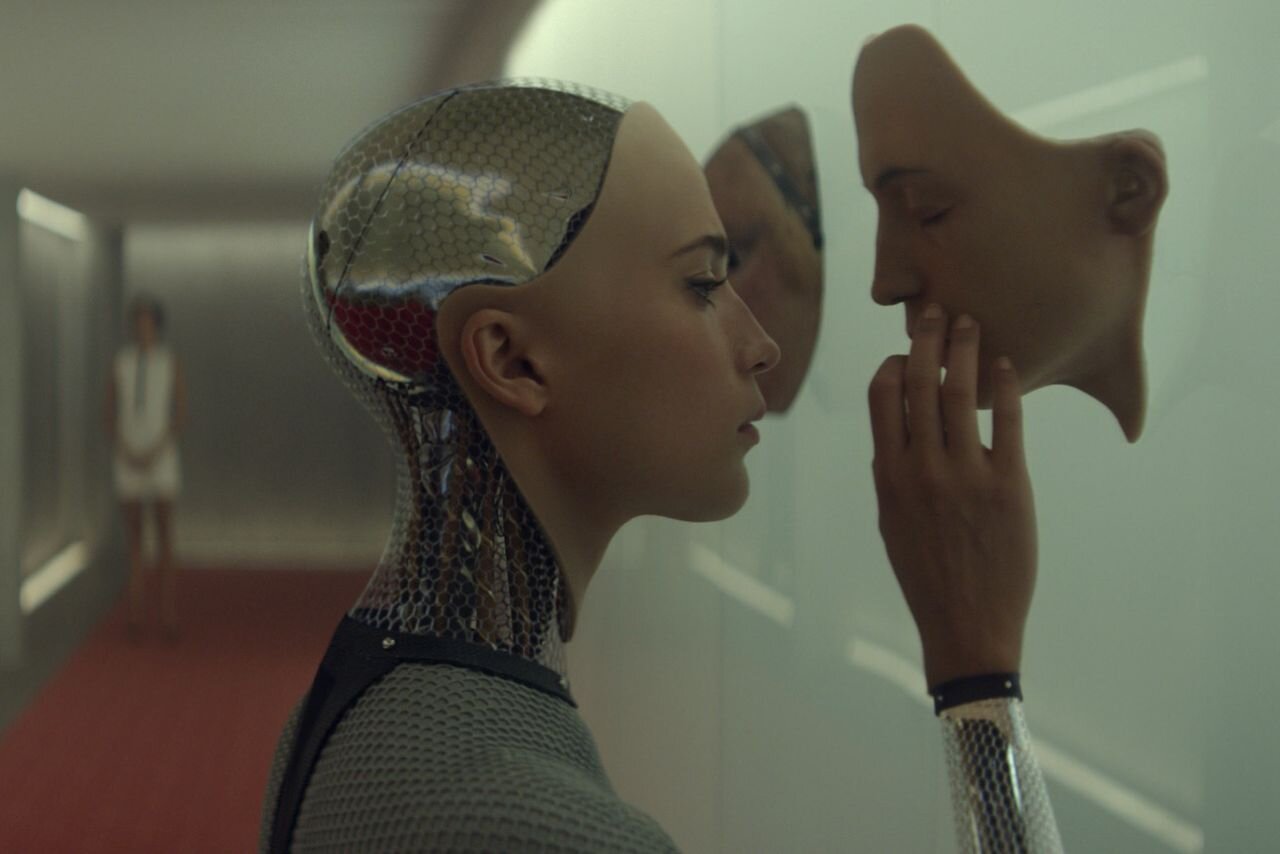

When it comes to Ex Machina, though, I also know that the reason I hadn’t watched might have been because it was released at a time when I was dealing with my own stupid issues; when you’ve got a brain tumour and you’re getting your skull drilled open, the last thing you want to watch is a thinking-man’s narrative about right and wrong, and dealing with a robotic character whose very design (as you can see above) suggests that her own head has been cut open a few times.

But Ex Machina isn’t any of those things, and I’m somewhat sorry that I waited until now to watch it. But only somewhat; I’m also happy to have left this film until now, giving me the time to truly and properly appreciate a rather simple story that goes deeply into the very idea of identity and humanity. As a matter of fact, from a creative point of view, I’m writing this wondering if and how this would or could be performed on the the stage with a definite sense of a singular location and time.

Domhnall Gleeson play Caleb, a coder who wins a sweepstake to spend a week with Nathan (Oscar Isaac), the high-ranking entrepreneur who has built and owns the company where Caleb’s works (and is probably so low down the pecking order that Nathan has no idea of who Caleb is.) Caleb is flown by helicopter to Nathan’s private and remote (but somewhat automated) estate; we’ve an impressive commute of mountains and ice combined with rain forest-type areas, the type of landscape of a very very rich man. Nathan’s business is a search engine, and the film isn’t subtle with calling attention to the high amounts of money and data that Nathan has access to.

Later in the film,Nathan reveals that there was no sweepstake; Caleb has been chosen specifically from Nathan’s staff based on his search results, including his taste in porn.) The relationship between Nathan and Caleb, initially painted as a man meeting his idol, quickly turns into one of those “never meet your heroes”-scenarios wherein Caleb tries making conversation with Nathan about work and creativity, only for Nathan to be too busy (and uninterested) while working out. The following day, the corporate side of things is revealed, with Nathan presenting Caleb with a legal document requiring his silence before, during and after working on their special project.

That project involves a newly built robot, with a very human body; played by Alivia Vikander, Ava is Nathan’s attempt to, effectively, create life, and Caleb has been summoned to help test her and see if she would pass the Turing test.

With all of this established, the movie is somewhat simple with its narrative, with none of its characters being particularly deeply developed. Nor is it needed for them to be; both Caleb and Nathan are painted as little more than Everyman-characters, with Caleb, a somewhat innocent man,stunned by nearly everything he sees and experiences, while Nathan is tired, broken and cynical, in a fashion that makes it difficult for both Caleb and the viewer to connect.

In doing so, Ex Machina paints Nathan as something of a villain and this is backed up in private conversations between Ava and Caleb. The film does little to establish any sense of depth to either Caleb or Nathan or their status as hero and villain. There is no likeable element to Nathan that could make him in any way salvageable or likeable, save for the wealth and the Oscar Isaac-ness, the guy is a completely horrible dick, especially towards housekeeper and chef Kyoko (Sonoyo Miauno). But he is nonetheless confident and powerful and in comparison, Caleb’s character comes across as somewhat pathetic and powerless; sure, he’s the hero that the film wants us to like, but there is little enough character there to make him wholly likeable or relatable.

That shouldn’t come across as a negative, as both the film (and Caleb) are aware of this. Ex Machina is a film that wants its viewers to question its characters and humanity, so it is fitting that, after the film throws those suggestions, hints and theories to its audience, Caleb questions his own identity, wondering if Ava is actually being used to Turing-test him.

Such a character beat briefly turns Ex Machina to an air of body horror as Caleb cuts himself, questioning his scars and his absent family while he queries his own humanity. The film impressively manipulates both Caleb and its audience, and it’s an act that works surprisingly well, if only because we, the audience, care more about Caleb and Nathan than about Ava herself.

Ava’s humanity, or attempts to find it, are told to the audience solely through Caleb and Nathan, and most viewings of her are seen through their eyes; both men are shown watching her through cameras and videos throughout the film with her usually doing nothing more than sitting there, showing no real humanity or sense of character. Because of this, she is entirely subject to the male gaze, barely allowed to be a whole individual character. Watching Ava through Caleb’s eyes, the audience is forced to become and invest in him and the relationship between them both, not in any existence in her own right.

This makes the relationship between Caleb and the audience somewhat problematic and he never rises to the challenge of becoming the hero of this narrative: at one stage Ava asks Caleb to close his eyes while she puts on a wig and clothes in an effort to pose as human. After she has left the room, Caleb opens his eyes and watches her in her moments of sanctuary; while the viewer does not see the scene from Caleb’s exact point of view, we both see an air of humanity within Ava as she tries to become human and, by insisting that he watch, Caleb steals this from her.

A similar scene plays out later in the film after Caleb and Ava have made their attempts at escape; Ava uses the bodies of previous models (including Kyoko) to cover her robotic components and pose as human, in many ways (re)creating herself. In doing so, she takes ownership of her identity and body away from Nathan and, indeed, any man. With that feminist beat in mind, Caleb watches this scene in a fashion that is intentionally provocative, both intimate and invasive at the same time, a scene that shows Ava as a powerless and somewhat child-like character, completely naked and exploring (or creating) her own body, while Caleb and the viewer watch (and watch her form duplicated in mirrors too) as if we are all refusing to give her that privacy.

That’s right, reader; I’m still talking about a very naked woman.

Caleb’s reaction to Ava’s new body is one of awe, although perhaps somewhat asexually so. In doing this the film continues to walk a line wherein Caleb’s reactions to Ava are uncomfortable: there is no consent, no respect in this behaviour. Impressed as Caleb may be with what he sees, he once again refuses to give Ava any privacy, never allowing her to have authority over herself; he sees her only by her gender, her body, her very essence. But never her identity.

Such nudity and reaction is a game-changing moment within Ex Machina not only because it allows Ava to become a fully recognised character, but in doing so, removing the sense of Other and remaking her as a fully fledged human with no more visible components to make her alien to the viewer.

While Nathan and Caleb remain Everymen with nothing unique in either, Ava passes her Turing test, proving her humanity to both the audience and to Caleb.

And then Ava rises above the Everyman, ensuring that the viewer is aware of this, watching her escape confinement and leaving Caleb trapped and alone to suffer. The film’s finale is a significant gender statement, with the female and robotic Ava bringing the Age Of Man (and Men) to a close. The film’s earlier mentions of divinity and godhead in previous conversation between Caleb and Nathan leave such ego for those men as Ava rises above masculinity and humanity to create her own future, a future that is controlled by neither man nor Man.

It’s a slightly different statement than that as delivered by Westworld, but the two narratives tell a similar story in which mankind itself may indeed be the villain.

And to think; Ex Machina managed to make that statement in a far quicker and resolute delivery than a TV show that encouraged me to write about a man’s penis.

Dammit, I promised I wouldn’t…